Seeking Safety Based Collateral Groups for Caregivers of Adolescents and Young Adults with Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health Diagnoses (CA UCEDD)

December 10, 2018

|

This is the second installation in a three-part series describing the structure, format, and development of social skills groups and parent collateral groups for individuals ages 13-21 with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), as well as the vital necessity of advocacy and community partnerships in working with our clients and their families. The first installation entitled, "Social Skills Groups Adapted from Seeking Safety Model for Adolescents and Young adults with Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health Diagnoses" was presented in AUCD360 in September 2018. Mental health providers from the University of Southern California University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (USC UCEDD) and the Children's Hospital Los Angeles Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine (DAYAM) have adapted Seeking Safety to promote social skills development among adolescents and young adults with developmental disabilities (DD) and co-morbid mental health diagnoses. In the first installment, we focused on the social skills groups based on the Seeking Safety intervention. In this article, we will provide an overview of our collateral parent groups and how to address a crucial area of need for both formal and informal sources of support for caregivers of individuals with IDD.

Although parenting youth with developmental disabilities often consists of resilience, joy, and fulfilment (Blacher, Baker, & Berkovits, 2013), parents also do face extra stressors such as attending multiple appointments, accessing therapies, coordinating with schools, and managing behavior and emotional regulation problems in the home. Parental stress may be particularly high during important events such as the time of diagnosis, as parents' and youths' age, and during the transition to adulthood services (Turnbull, Erwin, Soodak, & Shogren, 2011). Studies have shown increased parental stress when youth with developmental disabilities show more irritability, experience more health problems, and have more sleep problems (Valicenti-McDerm et al., 2015) and when parents have less access to social support and socioeconomic resources (Rubin & Crocker, 2006). Parental stress is linked with poorer physical and mental health outcomes for parents themselves (Allik et al. 2006; Schieve, Blumberg, Rice, Visser, & Boyle, 2007). Recently, a study examined the impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for parents of young children with developmental delays and found significant decreases in stress and depression levels as well as fewer reported ADHD and attention problems for their children compared to a waitlist control group (Neece, 2014).

Parents of adolescents with developmental disabilities in our clinic report a high prevalence of stressors and traumatic experiences that can impact their own emotional well-being as well as their parenting behaviors. Examples of common stressors in our parent population include low socioeconomic status, unemployment, insecure housing, lack of immigration documentation, and living with physical or psychiatric disabilities. Examples of traumatic experiences include intimate partner violence, exposure to war, gang, or community violence, and learning of sexual abuse of their youth. Parents have described how their stress and trauma history can impact their own emotional well-being and health, and interfere with their ability to manage their own emotions when working to use positive parenting practices with their youth or advocating for their youth in the context of unfamiliar, often unresponsive systems of care.

Social skills training has quickly become one of the most utilized approaches for addressing social communication and relationship issues for adolescents with ASD. However, many times parents have not been involved in the interventions though parents may provide vital support for the practicing of social skills and encouraging engagement in social activities. The UCLA PEERS program is one intervention modality that incorporates parents into treatment both in the group session and in the supporting youth with completing weekly socialization homework and providing social coaching when needed. In their study of PEERS with twenty-eight 12-17 year-olds with High Functioning Autism and their parents, Laugeson and colleagues (2012) found an overall improvement in social skills as reported by parents and teachers, as well decreased ASD symptoms related to social responsivity and increased social skills knowledge. While there have been fewer studies examining the efficacy of pairing parent group components with social skills groups for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders, there is growing evidence that doing so can lead to greater emotional awareness and problem-solving skills as well as decreases in depression reported child behavior problems (Solomon, Goodlin-Jones, & Anders, 2004). Further, identifying sources of formal and informal support have been found to mitigate the negative impact of the myriad stressors experienced by parents of youth with developmental disabilities (White & Hastings, 2004). In the present article, we aim to describe the format and structure of our clinic groups as a potential model for other community mental health centers that provide social skills training and support groups for youth with developmental disabilities and their families.

The Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine Behavioral Health Program hold four weekly social skills groups for clients ages 12-21. As described in the previous installation of this series, our social skills groups aim to augment social skill development, provide opportunities for experiencing peer support, and increase positive coping for managing emotional distress related to social isolation, bullying, and other types of trauma. Our groups are based on the structure of Seeking Safety, which is an evidenced-based therapeutic intervention that was designed to be implemented in an individual or group format and targets maladaptive coping, such as substance use or self-harm behaviors, and trauma-related symptoms (Gatz et al., 2007; Najavits, 2002).

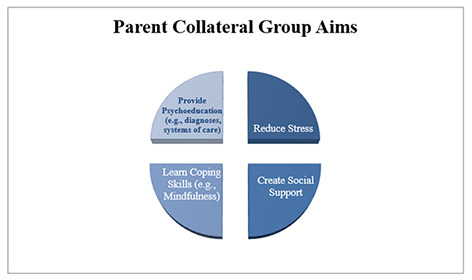

Two of the parent groups are held concurrently with the social skills group and two are held separately at other times. This is due to the fact that not all youth are able to participate in the groups due to verbal ability or present treatment needs. Regardless of youths' group participation, we invite parents to participate in the collateral groups given the benefit for both caregiver and youth. Clients are referred to these groups by their primary mental health clinician if the client is assessed to have any social skills deficit or impairment, potentially traumatic experiences (e.g., bullying, social exclusion, exposure to community violence), and would benefit from instruction and support in a social environment with like peers. The group facilitators meet with the clients prior to their joining the group to determine which of the groups would be most appropriate based on language and communication skills, social skills, and developmental age. The groups are ongoing and are not closed, such that parents may join at any time. The parent collateral groups seek to support parents in learning stress management techniques, accessing social support from peers, addressing advocacy needs through connection with local resources and agencies, and learning strategies for supporting their youth's mental health goals. Another aspect of the parent collateral group is the inclusion of guest speakers and community partners that provide education, advocacy strategies, scaffolding around accessing services, and recommendations empowering parents to independently navigate the cumbersome systems that they often encounter. To reflect the diverse community that we serve, these parent collateral groups are conducted in both English and Spanish.

Based on the needs of this particular population, group facilitators developed content for specific learning modules in the core topic areas of adolescent development, positive coping, psychoeducation related to diagnoses, navigating systems, and trauma-informed parenting. Within the area of adolescent development, facilitators discuss normative adolescent experiences, brain development, sexual health, identity development, and healthy relationships. Often times, parents of youth with developmental disabilities struggle with understanding, processing, and accepting their child's diagnosis(es), and thus, benefit from a space in which to receive psychoeducation and resources to support them through this process. Further, facilitators utilize the group space to introduce mindfulness and positive coping techniques to reduce parental stress, caregiver fatigue, and promote self-care and overall well-being. We also highlight the importance of modeling positive coping and self-care for their youth to improve their mental health outcomes. As our community is highly impacted by traumatic experiences (e.g., community violence, domestic violence), our group content includes a discussion of trauma-informed parenting focusing on the impact of trauma on youth development and how parents can support healing and growth from traumatic experiences. Moreover, we provide psychoeducation on intergenerational trauma, which can further impact family systems and mental health. We aim to reduce the influence of parental trauma histories on youths' emotional well-being and help parents to identify the role that their past trauma plays in their parenting strategies and how they view their children. Lastly, the group content encourages parents to be active participants through increasing their understanding of parent and youth rights, their roles in various systems, and strategies for effective communication with different providers.

Thus far, parents have provided overwhelming positive feedback regarding these collateral groups. Specifically, they have identified significant benefit from having a consistent peer support system that have shared experiences. Parents report using the space to process the trauma related to receiving a diagnosis and the impact on their family dynamics, functioning, and their vision for the future. Parents describe the groups as being both informal and formal sources of supports, such that they receive information and support from facilitators but also have access to their peers outside of the group setting. For example, some parents have connected and gone together to school and Regional Center meetings to provide each other with emotional support and assistance with advocacy. Parents also share their personal experiences with each other, allowing for validation of struggles, obstacles, and grief, which promotes a collective sense of community and belonging, as well as providing support for the development of resiliency.

As facilitators, we observed that having weekly parent collateral groups assisted with youth attending their own groups consistently and increased overall group retention. We also learned much about the importance of trust and relationship building with the parents and caregivers of youth in our groups. Particularly, we learned that gaining parental input helped to shape and tailor the content of our youth groups and informed the increased focus on advocacy and building community partnerships. In reflecting on our efforts in collaboratively developing content for collateral groups with the parents, we noticed the sheer amount of effort that was being put into educating caregivers about systems of care and engaging in effective advocacy efforts for their youth. In sum, our efforts have highlighted the vital need for collateral groups to partner with community agencies and provide such advocacy training, which will be described in greater detail in the third and final installation of this series.

References

- Allik, H., Larsson, J. O., & Smedje, H. (2006). Health-related quality of life in parents of school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 1-8.

- Blacher, J., Baker, B. L., & Berkovits, L. D. (2013). Family perspectives on child intellectual disability: Views from the sunny side of the street. The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability, 166-181.

- Gatz, M., Brown, V., Hennigan, K., Rechberger, E., O'Keefe, M., Rose, T. & Bjelajac, P. (2007)

- Effectiveness of an integrated, trauma-informed approach to treating women with co-occurring disorders and histories of trauma: The Los Angeles site experience. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(7), 863-878. DOI:10.1002/jcop.20186

- Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with Autism Specturm Disorders: The UCLA PEERS Program. Journal of Autism and Development and Disorders, 42, 1025-1036.

- Najavits, L.M. (2002). Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. Guilford Substance Abuse Series. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Neece, C. L. (2014). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: Implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27 (174-186).

- Rubin, I. L., & Crocker, A. C. (Eds.). (2006). Medical care for children & adults with developmental disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

- Schieve, L. A., Blumberg, S. J., Rice, C., Visser, S. N., & Boyle, C. (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119(Supplement 1), S114-S121.

- Solomon, M., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., & Anders, T. F. (2004). A social adjustment enhancement intervention for High Functioning Autism, Asperger's Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder NOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(6), 649-668.

- Turnbull, A. P., Erwin, E., Soodak, L., & Shogren, K. A. (2011). Families, professionals, and exceptionality: Positive outcomes through partnerships and trust. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Valicenti-McDermott, M., Lawson, K., Hottinger, K., Seijo, R., Schechtman, M., Shulman, L., & Shinnar, S. (2015). Parental stress in families of children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of child neurology, 30(13), 1728-1735

- White, N., & Hastings, R. P. (2004). Social and professional support for parents of adolescents with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17, 181-190.