Knowledge Translation in Action: Making Research More Accessible (MT UCEDD)

May 4, 2018

|

To read this post on the RTC:Rural website, visit Knowledge Translation in Action: Making Research More Accessible.

To translate: to take something written in one language and express it in another. Or, to change something into a new form. This is precisely what RTC:Rural's Knowledge Translation team does.

Knowledge Translation is an important part of making sure RTC:Rural's research is accessible. Accessibility doesn't refer to only alternative formats, such as Braille or screen-reader friendly-it's also about making sure the content is easily understood, relevant, and useful to the people who are reading, viewing, or listening to that information. RTC:Rural's Knowledge Translation team works to make sure that all RTC:Rural research is in the best format for its intended audience, be they people with disabilities and their families, service providers, other researchers, or policy makers.

RTC:Rural uses Knowledge Translation throughout the entire research process, from the research design phase to disseminating the final results. One recent example of this is in the collaboration between Knowledge Translation and the Effort Capacity and Choice project team. The Effort Capacity and Choice project examines the relationship between personal effort and community participation. To do so, the project studies the impacts of two interventions. In the Home Project Intervention, researchers install adaptive bathing equipment in the participant's bathroom, reducing the amount of effort it takes to bathe and use their bathroom. In the Exercise Project Intervention, participants receive physical therapy in order to increase their physical capacity.

During a regular project update meeting, Research Associate Andrew Myers, the project lead, mentioned to Knowledge Translation Associate Lauren Smith that he often fielded calls from participants in the middle of the study wanting clarification about what they were supposed to do next. Due to the project design, participants could be waiting a week (for the Home Project Intervention) or months (for the Exercise Project Intervention) between project phases. For more on these interventions, see "Does your bathroom routine drain your battery? How effort and exercise shape community participation."

Myers and Brendan Hogg, a Health and Human Performance graduate student at the University of Montana who is working on the project, also identified a need to have better materials to share during the recruitment process. "Brendan is great at explaining the project to participants during the initial meeting, but it's easy to forget those details weeks, or months, later," said Myers. After this initial meeting, which includes training on how to use electronic survey devices, participants are given a packet of information about the project. However, it can be hard to scan through the multi-page consent form to find the specific information they might be seeking.

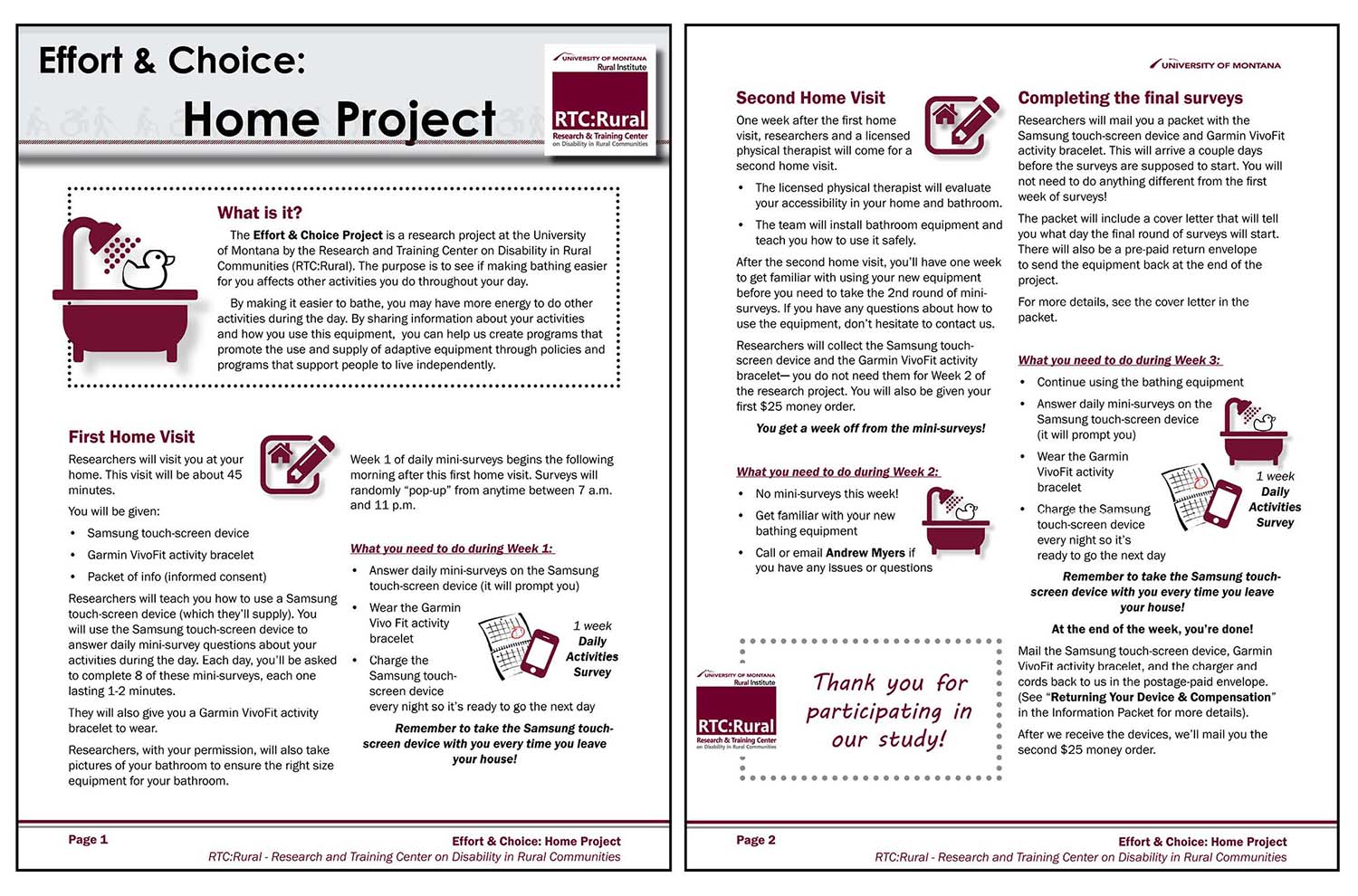

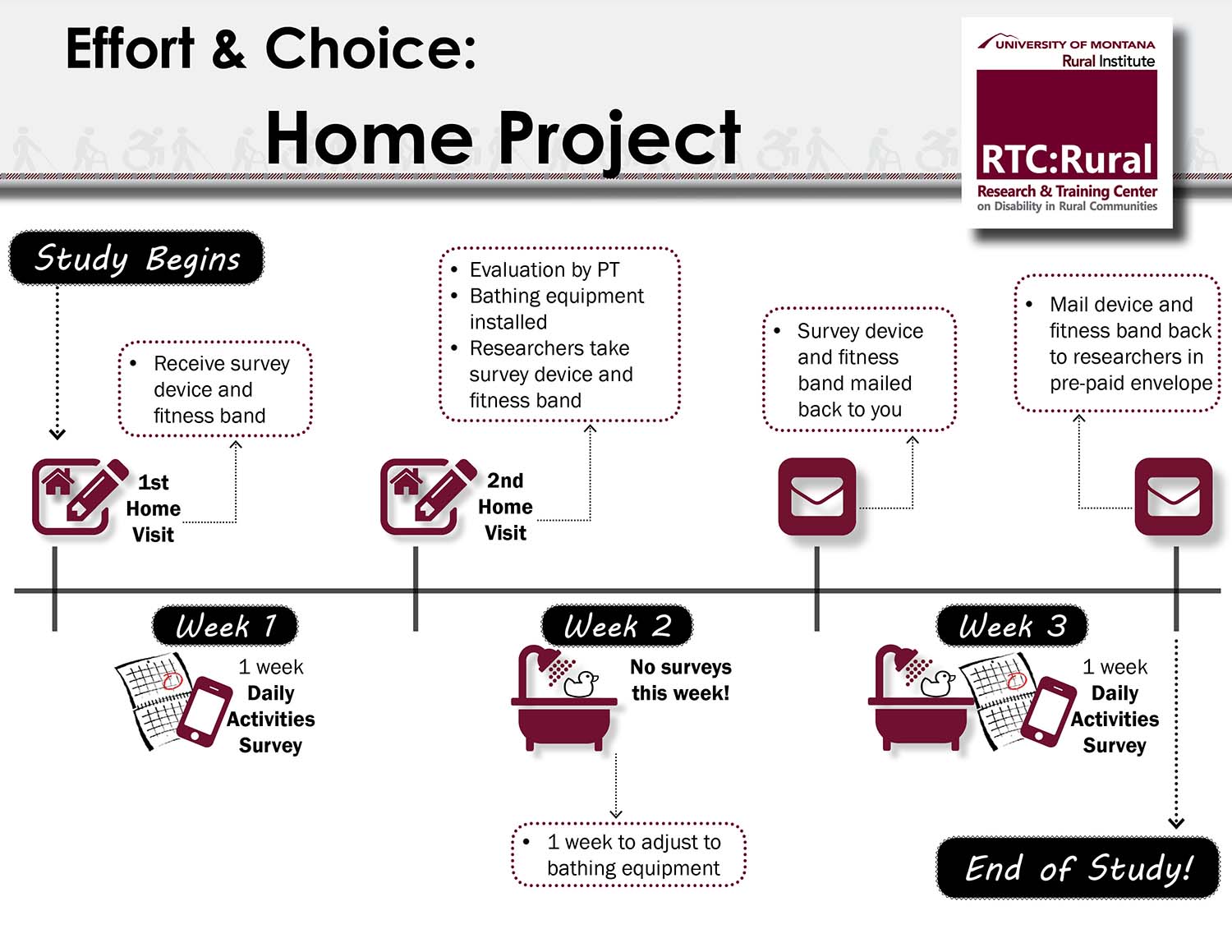

Upon hearing this, Smith proposed to create easy-to-reference, accessible documents for participants to use as references over the course of the project. Working closely with Hogg and Myers, Smith took the detailed information from the consent form given to participants at the beginning of the study and designed two documents. The first is a one page (front and back) informational handout that describes the purpose of the study and provides simple directions for each step of the intervention. The second is a one-page timeline, showing key events and the order in which they happen.

"The idea was that these documents could be a quick, easy way to remember what you're supposed to be doing," said Smith. "You could put the timeline on your fridge, and there's space on it so you could write in the exact dates of when the project starts and finishes."

"Growing up in a household with disability, I understand how challenging it can be to balance the daily tasks of caregiving for yourself or others with employment and school responsibilities, household chores, and other activities," said Smith. "I wanted to help make sure it is as easy as possible for the participants. It's another way we can acknowledge that we respect and value their time-by creating easily-accessible content."

"Of course we encourage participants to call if they have any specific questions or issues during the project," said Myers, "but these documents are a nice way to answer some of the general questions participants might have."

Below are examples of the Home Project intervention documents. Links to text-only files and text descriptions are below each image.

Click on the links below for the PDF of this document or to access a PDF text-only version.

PDF: Effort & Choice: Home Project (not formatted for screen readers)

PDF: TEXT ONLY Effort & Choice: Home Project

Click on the link below to access the text description of this graphic.

PDF: Effort & Choice: Home Project timeline (not formatted for screen readers)

HTML: Link to text description of Home Project Timeline

Myers and his team have integrated these documents into their regular training manuals. The documents help guide the conversation between the researchers and the participants, making it easier for researchers to explain the project as well as easier for participants to understand. By helping participants better understand and remember the research protocol, these products ensure that participants will have better experiences, which will allow researchers to collect better data. This data, in turn, may one day influence solutions and policies that will help others live independently and participate more fully in their communities.

To learn more about RTC:Rural's Knowledge Translation efforts, visit the Knowledge Translation page on the RTC:Rural website.

For more about the Effort Capacity and Choice project, visit the Effort Capacity and Choice project page.